In April, the Trump Administration declined to expand coverage for anti-obesity medications in Medicare—a setback for millions of beneficiaries living with obesity. However, the Administration left open the door to explore alternative pathways to coverage.

It is vital that CMS pursue these alternatives. We have shown that expanded access to GLP-1s to treat obesity yields social returns of up to 20% annually for older populations. This makes GLP-1s one of the most effective public health investments available. Expanded access could also help the Medicare program address its pending insolvency: Our research also suggests GLP-1s could save Medicare up to $245 billion over 10 years by reducing demand for other services.

CMS—not unlike other payers—appears put off by the potential upfront costs. At list prices of $13,000 or more annually—and with millions of potential beneficiaries—spending could be quite high initially. While the treatment is available to those with diabetes or other cardiovascular risks, an indication for weight loss appears like a bridge too far.

There will be pressure on the Trump Administration to lower the price. Indeed, CMS will soon decide Medicare’s price for semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus) under Inflation Reduction Act negotiations. The Congressional Budget Office projects an average federal annual cost of $3,700 in the first year after Medicare negotiation.

But what is a fair price? We would argue that the appropriate price would reflect the underlying value of the treatment. The value-based price (VBP) should reflect the monetized value of the health benefits (to patients), reduced medical spending and increased productivity associated with treatment. Tying prices to value ensures a more rational system—one that rewards innovation for meaningfully improving patients’ health while potentially lowering prices of medicines that offer more modest benefits.

Here we report our estimates of a value-based price (VBP) for anti-obesity medications using the Future Adult Model, a dynamic microsimulation which has been extensively validated and applied to a range of policy questions.

What is the value-based price for Medicare?

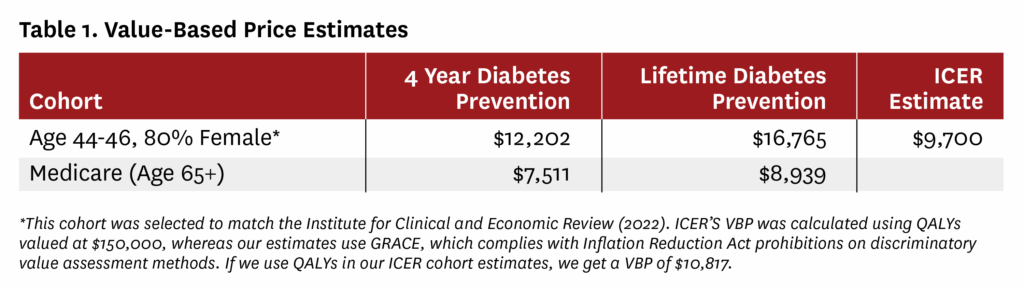

We estimate treating the Medicare-aged population would support a VBP in the range of $7,511 to $8,939 per year. The range reflects a difference in assumptions: Do GLP-1s prevent diabetes for four years (similar to clinical trial results) or will these benefits extend over a lifetime?

How do our estimates compare with ICER?

For a younger cohort of Americans (ages 44-46), who have a longer lifetime to enjoy better health, we estimate an annual VBP of $12,202 to $16,765. Again, the range reflects two different assumptions about how long anti-obesity medications prevent diabetes (four years or over a lifetime). We assumed this younger cohort is 80% female, consistent with modeling from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in its 2022 report estimating an annual VBP of $9,700.

A few key factors help explain why our estimate differs from ICER’s. First, we model a 20% weight reduction based on clinical trial results for tirzepatide (Zepbound and Mounjaro), while ICER estimated a 13.7% weight reduction based on evidence for semaglutide. Additionally, the FAM tracks a broader range of health conditions impacted by obesity. And unlike ICER, it avoids using discriminatory methods for assessing value such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which tend to favor treatments that help healthier patients. Instead, FAM makes value assessments using Generalized Risk-Adjusted Cost-Effectiveness (GRACE), which recognizes that sicker patients value health gains more than healthier patients. When we use QALYs, the VBP becomes $10,817, implying that the larger weight reduction and more inclusive accounting of obesity-related health impacts together add about 12% to the estimate of value, compared to ICER.

Where does the value come from?

For the Medicare population, most of the value is derived from patient health benefits, as shown in Table 2. Just over one-tenth of total treatment value comes from avoiding future medical expenses or increased earnings among healthier patients. However, there could be a larger earnings impact on a younger population since they have more working years ahead of them.

What might a value-based alternative look like?

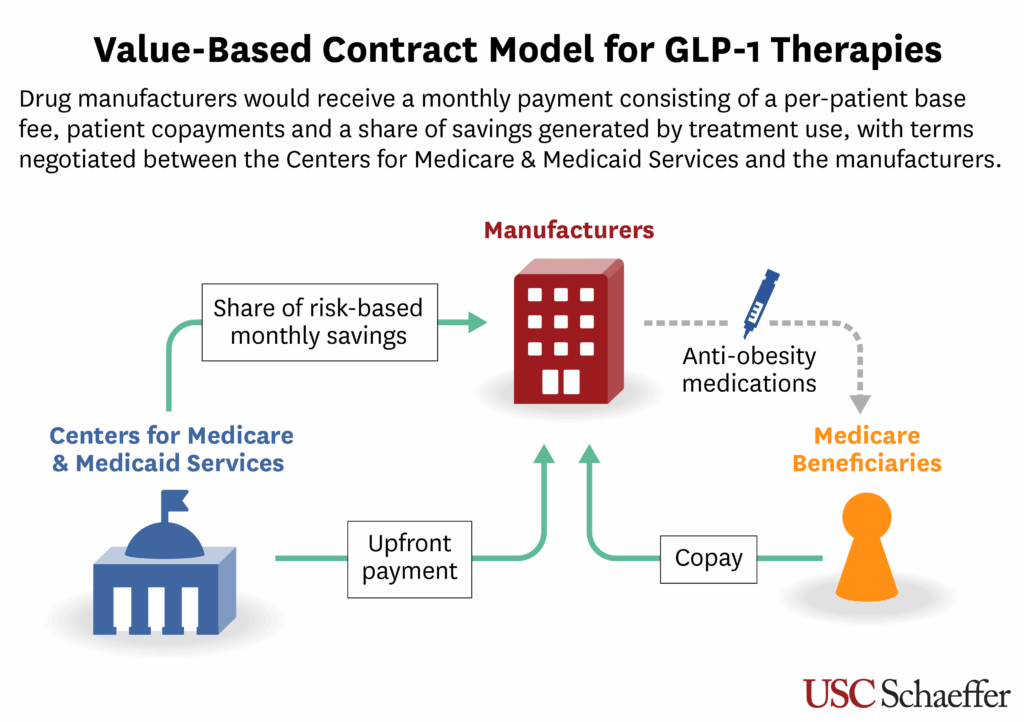

The federal government has other ways to expand access beyond price negotiation. In a separate working paper, we propose a value-based approach to expand GLP-1 coverage for weight loss. CMS would pay a lower upfront price while sharing Medicare long-term savings with manufacturers if and when they are realized.

For simplicity, we suggest a straightforward reimbursement approach. Manufacturers would receive a monthly payment that consists of three elements: a base per-patient fee, patient copayments and a bonus payment based on Medicare savings that accrued from GLP-1 use. The base fee and copayments would be subject to negotiations between CMS and manufacturers, along with other elements like contract length, patient population and inclusion of obesity-related conditions. The bonus component should account for a substantial share of potential payments and could be calculated using Medicare’s existing risk-adjustment infrastructure to identify savings from avoided obesity-related conditions.

Medicare savings and payments to manufacturers would get larger over time as more obesity-related conditions are avoided, with the largest savings coming from reductions in diabetes. Under a hypothetical contract in which Medicare and manufacturers share savings equally, traditional Medicare spending would be reduced by $24.3 billion in year 10, while manufacturers would receive $12.2 billion in bonus payments.

Value-based price estimates provide context around value-based contracting negotiations, because they represent the total per patient social value produced by the drug. This value gets split among manufacturers, third-party payers like Medicare, and patients, depending on how much of the social value accrues to each. Regardless of the specific contract that gets negotiated, the goal should be to help patients who need access, expand the market for manufacturers and address Medicare’s concerns about how these drugs will perform long-term. By centering this conversation on value, the decision will align all parties around a shared goal: lasting improvements in health.

How did we determine the value-based price?

Our model simulates lifetime outcomes for two nationally representative cohorts without diabetes who qualify for anti-obesity medications based on obesity status (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). We calculated the lifetime value from treatment divided by the number of treatment years. We assume a 20% long term weight reduction, consistent with findings from both SURMOUNT-1 and SURMOUNT-4.

The simulation, starting in 2025, projects lifetime trajectories of health, medical spending, earnings and disability payments, making it possible to calculate cost offsets and social value. We compared lifetime estimates under a status quo scenario where Medicare does not cover GLP-1s for weight loss and a scenario where Medicare expands access to all clinically eligible patients.

We generated estimates of a value-based price under two different assumptions about the long-term efficacy of GLP-1s in preventing or delaying diabetes. Our base-case model assumes a 94% reduction in diabetes incidence through the first two model cycles (four years), matching the reduction observed in a three-year clinical trial of tirzepatide. In all future years, diabetes incidence is predicted by FAM’s diabetes risk equation that accounts for BMI and other health and socioeconomic characteristics. (See the model’s full technical appendix). In a second treatment scenario, we assume that the diabetes prevention results from the clinical trial persist for the remainder of patients’ lives. Together, these two scenarios should provide an accurate range of possible value-based prices.

About our model: The FAM has been developed over several decades with funding from CMS, NIH, the National Academies of Science, the MacArthur Foundation and others. FAM and its predecessor models have been extensively validated, and FAM findings were prominently featured in two National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine reports. In other health contexts, FAM has been used to measure the benefits to delaying Alzheimer’s disease, the value of statins, preventing heart disease, better diabetes care, improved mobility and even the value of delayed aging.