Editor’s Note: This op-ed was originally published in STAT on June 12, 2025.

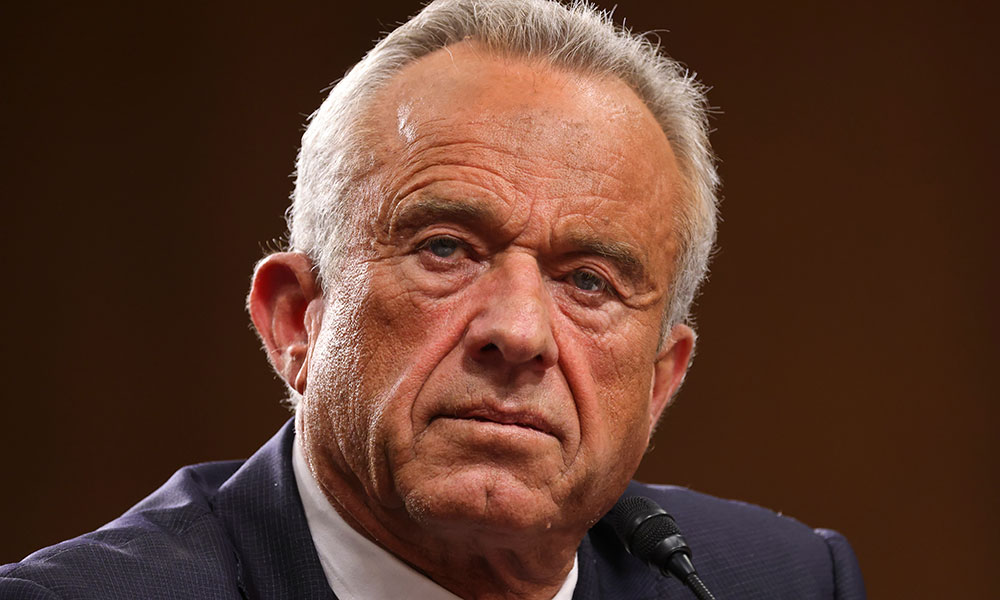

If Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. wants to “clean up the corruption and conflicts” at HHS, he is going about it the wrong way.

I study conflicts of interest at federal agencies. While industry influence is a widely shared concern, Kennedy’s dismissal of all the members of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine advisory committee, and the rapid hiring of eight replacements, could easily misfire.

The purpose of an advisory committee is to have external experts offer independent advice to the government on technical and scientific issues. These experts are typically faculty or researchers at universities and scientific institutes. A wholesale purge may remove members with industry ties, but it is not a costless get-out-of-jail card. Studies show that committee members with industry relationships tend to publish more and higher-impact articles, suggesting they can bring more expertise to the table. And in therapeutic areas where there are few researchers, such as rare diseases, it takes much more time and effort to find qualified people without financial conflicts. This results in delays in government decisions and ultimately patient access.

In studying conflicts of interest on FDA advisory committees, I found that, perhaps as expected, members with financial ties to the company with the drug under review were more likely to vote in ways favorable to the company.

What was surprising was that members with ties to both the sponsoring company and a competitor voted, on average, the same way as members who had no industry ties. Multiple financial ties didn’t necessarily make members more biased. It made them less biased, likely because of the counterweight introduced by competition.

The type of financial relationship also mattered. Being an advisory board member for a drug company was associated with a lot of bias, but other kinds of ties, like some kinds of research support, were not.

If Kennedy really wants to limit industry influence in health policy and the health care system, the most impactful thing he could do is to roll back the funding cuts at the National Institutes of Health. Cutting-edge medical research at universities is supported by grants, predominantly from NIH and the federal government. If researchers cannot find research funding from NIH, they will go elsewhere. Some may seek grants from foundations, but foundations don’t have nearly the budgets needed to replace NIH funding.

Who does have the money and is willing to spend it? Drug companies. Don’t be surprised if Kennedy’s NIH cuts lead to an epic shift of medical research toward Big Pharma funding — precisely the opposite of what he says he wants.

And if the secretary wants to restore public trust in and maintain the integrity of health agencies, he should immediately make good on his “radical transparency” pledge and apply it to all health advisory committees, including the newly constituted vaccines advisory committee. The public should know how the members were recruited, who was recruited but declined, how members were selected, and of course, any financial relationships with potentially affected parties. This includes ties to not only vaccine, drug, and device manufacturers, but also companies offering alternative therapies and other services that are competitors or complements to the products under review. Prior to each meeting, the agency should release financial disclosures for all members attending and voting, as well as for those who are excluded from voting because of conflicts. If the agency does not, the members themselves should release their disclosures or waivers.

Ridding the government of industry interests need not rely on the indiscriminate wielding of axes. Scalpels and sunshine — and a genuine commitment to a holistic approach — can buttress public trust in our health agencies and our health care system.

Genevieve Kanter is a senior scholar at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics and associate professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy. She studies conflicts of interest in government and does not have any financial relationships with vaccine, drug, or device manufacturers. She has received a grant from Arnold Ventures to study an unrelated topic about FDA advisory committees.