Joyce explains why patients’ drug costs may vary from pharmacy to pharmacy

Narrower Coverage of MS Drugs Tied to Higher Relapse Risk

Broad formulary exclusions of specialty drugs may make it harder for chronic disease patients to get the treatment that works best for them

Medicare drug plans are increasingly excluding coverage of new specialty drugs that treat complex conditions like cancers and autoimmune diseases. New research from the USC Schaeffer Center shows how these barriers may come at a cost to patients’ health.

In a large study of Medicare beneficiaries with multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers found those in plans with broader coverage of MS treatments had significantly lower risk of developing new or worsening symptoms months later. The findings, published Aug. 1 in JAMA Network Open, suggest that plans with narrower coverage of MS treatments may be linked to worse health outcomes.

Pharmacy benefit managers, who negotiate drug benefits on behalf of plans, often leverage the threat of excluding a new medication from their list of covered drugs, or formulary, to extract deeper manufacturer rebates or discounts. While this can be an effective strategy to contain costs when cheaper generics or similar options are available to patients, it can be problematic for complex conditions since treatments often work differently in each patient.

“Patients with MS may need to try multiple drugs to find what works best for them. Broad formulary exclusions ultimately undermine the individualized care these patients need,” said lead author Geoffrey Joyce, director of health policy at the Schaeffer Center and chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical and Health Economics at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Widespread formulary exclusions

Numerous medicines have been approved in recent years to help patients manage symptoms of MS, a potentially debilitating disease that attacks the central nervous system. While there is no cure, a growing number of treatments can help slow disease progression, reduce relapses and limit new disease activity.

As of 2022, there were 15 oral and injectable MS drugs across seven types of “classes,” or groups of medication that work in similar ways. These treatments are all pricey, usually costing $5,000 to $10,000 per prescription, though some range much higher. Since they are not included in Medicare’s “protected classes” of drugs, private insurers that administer Part D plans have greater leeway to refuse coverage or impose restrictions on their use.

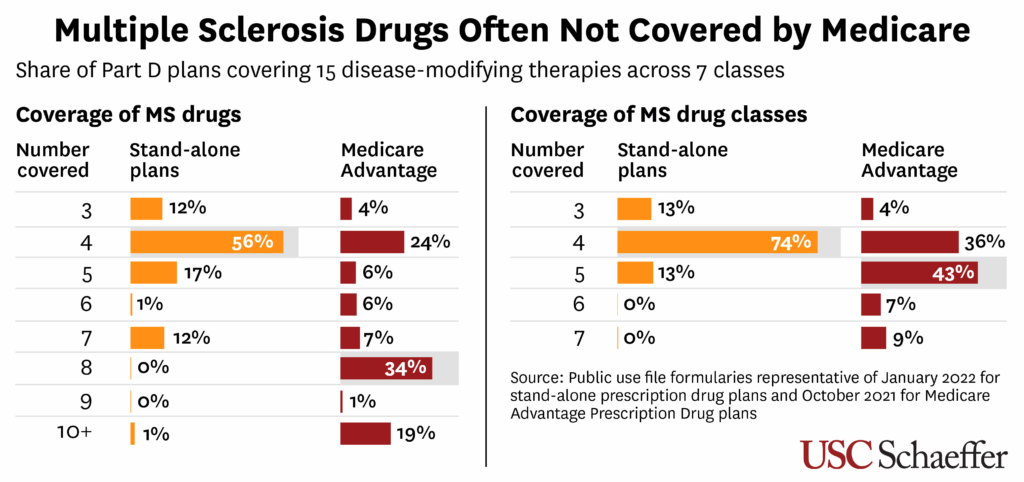

The researchers examined drug coverage for 85,000 Medicare beneficiaries with relapse-remitting MS—the most common form of the disease, marked by periodic flare-ups of neurological symptoms. The beneficiaries either received Part D coverage through a stand-alone plan or as part of a more comprehensive Medicare Advantage plan in the previous year. Researchers found:

- Stand-alone plans most commonly included just four of the 15 available drugs (across four classes) on their formulary. Medicare Advantage coverage was broader, typically covering eight drugs across five classes.

- Just a few drugs were covered by nearly all Medicare plans, while many others were excluded by almost all stand-alone plans and most Medicare Advantage drug plans. That includes older drugs like teriflunomide, which was approved in 2012.

- For those in Medicare Advantage drug plans, having broader formulary coverage was associated with 8-12% lower odds of MS relapse during the current quarter. For those in stand-alone plans with broader coverage, the odds were 6-9% lower.

Alternative financing options may help expand access

The researchers warned that formulary exclusions for specialty drugs could become more widespread under Part D’s new out-of-pocket cap, which limits beneficiaries’ annual drug spending to $2,000 per year while shifting more costs onto plans. Since only covered drugs count toward the cap, plans may be further incentivized to exclude high-cost treatments.

Creative financing strategies for such medications could encourage broader coverage, the researchers said. For instance, arrangements that link payments to health outcomes or subscription-based models in which insurers pay a flat fee to manufacturers for unlimited access to a specific drug or set of drugs could help plans manage the long-term costs of specialty drugs.

“Innovative new treatments have made it possible to slow or prevent symptoms for some of the most complex diseases, but costs remain a challenge,” Joyce said. “We must find sustainable ways to ensure all patients can access these potentially life-changing treatments.”

About the study

The study was also co-authored by Barbara Blaylock of Blaylock Health Economics LLC and Karen Van Nuys, a retired senior scholar at the Schaeffer Center. The research was supported by grants from the American Medical Association and grant R01-AG055401 from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health.

Eye on PBMs

Following the Money

Schaeffer research reveals how inefficiencies in the drug supply chain increase costs and limit access

Our Research on PBMsDelinking PBM Compensation From Drug List Prices Could Unleash Major Savings

Reforming payments to PBMs and other pharmacy middlemen could lower annual U.S. drug spending by nearly $100 billion, analysis finds

Breaking the link between prescription drug list prices and compensation to middlemen like pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) could cut a significant portion of the nation’s annual drug tab, finds a new analysis from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

PBMs, who negotiate drug benefits on behalf of insurers and employers, are typically paid based on a percentage of a drug’s list price before rebates and other discounts are applied. Federal and state policymakers have proposed delinking PBM compensation from list prices in response to evidence that PBMs often steer patients toward higher-priced drugs — even when cheaper alternatives are available — to boost their own profits.

Shifting instead to a transparent, fixed payment model for PBMs and other intermediaries in the prescription drug supply chain would reduce annual net drug spending by $95.4 billion (or nearly 15%) without undermining pharmaceutical innovation, according to research from Schaeffer Center Director of Health Policy Geoffrey Joyce published July 24 in Health Affairs Scholar.

Fair Compensation

The U.S. spent $650 billion on prescription drugs in 2023 after factoring in discounts, with about one-third ($215 billion) flowing to PBMs, wholesalers and pharmacies — though the exact division of these costs is unclear. However, using simplified estimates, Joyce finds spending on these intermediaries would have dropped to $119.6 billion under fair and transparent compensation models.

Here’s how those costs break down:

PBMs: A fixed administrative fee of $4 per claim would result in total costs of $27.6 billion in 2023. Payments to PBMs could be reasonably adjusted for hitting cost and quality targets.

Wholesalers: Entities that purchase drugs from manufacturers in bulk add about a 3% markup on average to the list price before selling to pharmacies, hospitals and long-term care facilities. Applying that markup to net prices instead would yield $19.5 billion in total revenues, less than the $27.5 billion these firms reported in 2023.

Pharmacies: A $10.50 per prescription dispensing fee would have generated gross venues of $72.5 billion. That rate is commonly used by state Medicaid programs and aligns with the pricing model used by Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company.

Reform Implications

A proposal to delink PBM compensation from list prices was included in earlier drafts of sweeping domestic policy legislation before it was dropped from the final version that was recently enacted. However, policymakers have expressed continued interest in reforming PBM practices amid growing evidence that these firms use their considerable market power to artificially inflate drug prices and restrict access to essential medications.

Joyce warns that some commonly proposed reforms, such as those aimed at curbing consolidation and increasing PBM transparency, are too modest to meaningfully change PBM behavior given how quickly the industry has shifted tactics in the face of heightened scrutiny.

“Delinking compensation from list prices is the clearest and most effective way to tackle the warped incentives in the prescription drug supply chain that drive up costs for patients without adversely affecting manufacturers’ incentive to innovate,” says Joyce, who is also chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical and Health Economics at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Eye on PBMs

Following the Money

Schaeffer research reveals how inefficiencies in the drug supply chain increase costs and limit access

Our Research on PBMsSood recommends key PBM reforms in testimony before U.S. Senate panel

California’s proposal to establish fiduciary duty for PBMs would be an important cost-saving reform, Joyce says

Testimony on Competition Issues in the Prescription Drug Supply Chain

Editor’s Note: The following is a testimony delivered by Neeraj Sood to the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary on May 13, 2025. More information about the hearing.

Key Points:

- A substantial portion of what Americans pay for prescription drugs is captured by intermediaries in the distribution system, some of whom neither develop nor directly provide these medications to patients.

- Vertically-integrated pharmacy benefit managers-insurers-pharmacies earn higher profits from their investments compared to the average firm in the S&P 500, suggesting lack of competition in these markets. This trend in vertical integration raises significant antitrust concerns.

- Our study of the insulin market shows that PBMs are doing part of their job—negotiating lower prices from manufacturers—but failing at another crucial aspect: ensuring these savings benefited patients and the healthcare system more broadly.

- The current system of confidential rebates and rising list prices benefits all firms in the pharmaceutical supply chain at the expense of the American patient.

- Increasing price transparency, giving PBMs the fiduciary responsibility to act in the best of interests of health plans and their members, reforming rebates, and addressing antitrust concerns from vertical integration can help make the prescription drug market more competitive and work better for the American patient.

Full testimony is available. Schaeffer Center research on PBMs is available here.

Arkansas’ first-in-the-nation law banning PBM ownership of pharmacies should be implemented slowly to ensure access, Qato says

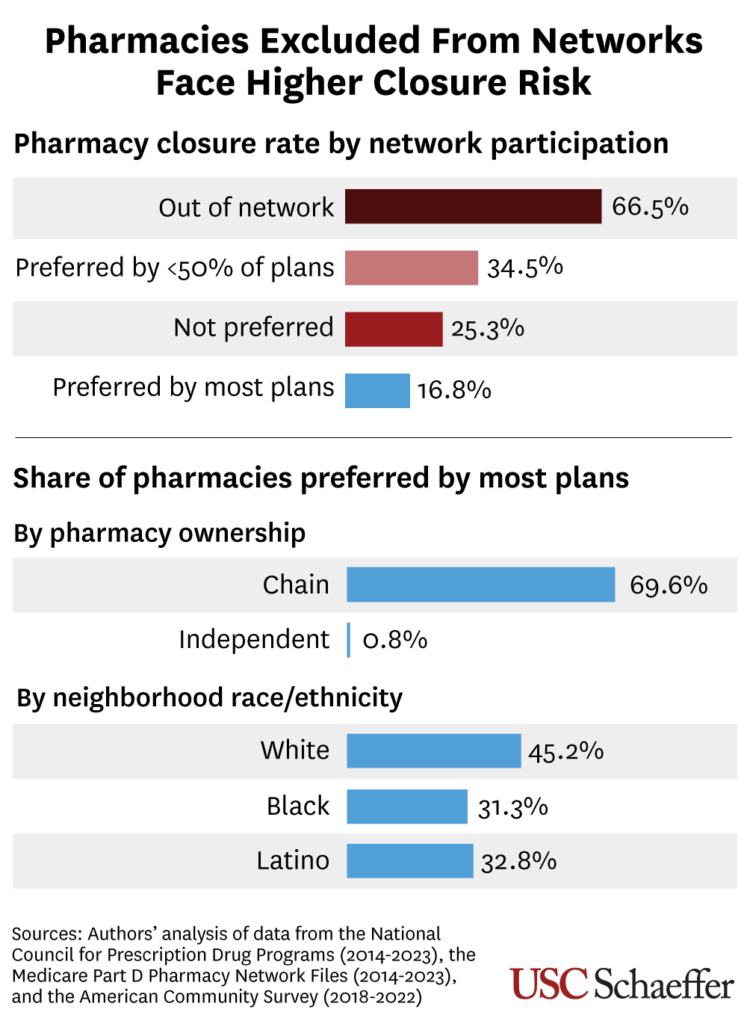

Pharmacies Excluded from Preferred Networks Face Much Higher Risk of Closure

Study reveals how Medicare Part D networks managed by drug middlemen are contributing to widespread pharmacy closures

Retail pharmacies excluded from Medicare Part D networks maintained by drug benefits middlemen were much more likely to close over the past decade, according to new research from USC published in Health Affairs.

Independent pharmacies and those located in low-income, Black or Latino communities were more likely to be excluded from “preferred” pharmacy networks, putting them at higher risk of closure, researchers also found.

The study is the first to examine how substantial growth of preferred pharmacy networks in Medicare’s prescription drug benefit may have contributed to the struggles of retail pharmacies, which the researchers in an earlier study found have closed in unprecedented numbers. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which control drug benefits on behalf of employers and insurers, steer beneficiaries away from non-preferred pharmacies by imposing higher out-of-pocket costs at those locations.

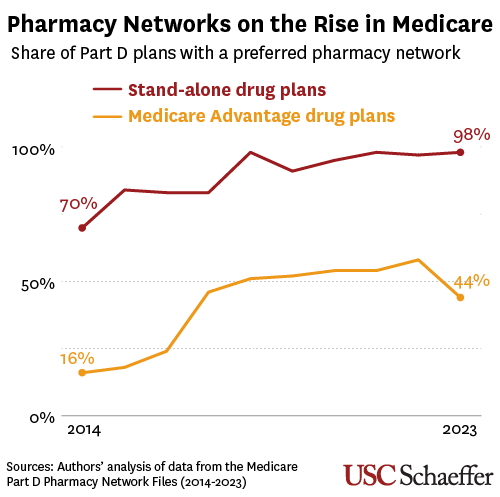

The use of preferred pharmacy networks tripled to 44% among Medicare Advantage drug plans over the past decade and grew from 70% to 98% among stand-alone Medicare drug plans, researchers found.

This shift coincided with a wave of mergers involving the nation’s largest PBMs and retail pharmacy chains, which may have incentivized PBMs to nudge patients to pharmacies they are affiliated with — and away from competitors. The Federal Trade Commission in an interim report last year alleged that PBMs “routinely create narrow and preferred pharmacy networks” to favor their own pharmacies and exclude rivals.

“Our study demonstrates that pharmacy networks in Medicare Part D — which are designed by PBMs — are contributing to the growing problem of pharmacy closures, particularly in communities that already lack convenient access to pharmacies,” said study senior author Dima Mazen Qato, a senior scholar at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and the Hygeia Centennial Chair at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Disparities in Network Participation

Researchers analyzed pharmacy closures between 2014 and 2023. Among their key findings:

- Pharmacies preferred by fewer than half of plans were 1.7 times more likely to close than those preferred by most plans in the past decade, after accounting for factors such as ownership and neighborhood demographics.

- Pharmacies not participating as preferred pharmacies for any Part D plan were 3.1 times more likely to close, and pharmacies that were entirely out of network were 4.5 times more likely to close.

- While 4 in 10 pharmacies had independent ownership in 2023, just 0.8% of these were preferred by most plans. Meanwhile, 70% of chain pharmacies were preferred by most plans.

- About 3 in 10 pharmacies in Black, Latino or low-income neighborhoods were preferred by most plans that year, compared to nearly half of pharmacies in higher-income or white neighborhoods.

- Network participation varies considerably across the country. In a diverse group of 13 states that includes New York and North Dakota, fewer than one-third of pharmacies were preferred by most plans.

Policy Implications

“Our findings demonstrate that there is a need for federal PBM reform to expand preferred pharmacy networks,” said the study’s first author, Jenny Guadamuz, an assistant professor of health policy and management at the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health. “New legislation might prove elusive but there may be room for regulator actions.”

The researchers point to actions the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could take, including considering provisions that ensure Part D plans meet preferred pharmacy access standards and mandating preferred status. Regulators and policymakers could also mandate increases in pharmacy reimbursement, especially for critical access pharmacies at risk for closure and if they are serving “pharmacy deserts.”

About This Study

Other authors are Genevieve Kanter of USC and G. Caleb Alexander of Johns Hopkins University. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R01AG080090). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. See the study for author disclosures.

Eye on PBMs

Following the Money

Schaeffer research reveals how inefficiencies in the drug supply chain increase costs and limit access

Our Research on PBMsMedicare Part D Preferred Pharmacy Networks And The Risk For Pharmacy Closure, 2014–23

Abstract

Medicare Part D plans incentivize the use of specific pharmacies through preferred networks. We found that independent pharmacies and pharmacies in low-income, Black, and Latinx neighborhoods were less likely to be preferred by most Part D plans than chains and pharmacies in other neighborhoods. Pharmacies that were not preferred by most plans were 70–350 percent more likely to close than other pharmacies.

The full study can be viewed at Health Affairs. A press release on the study is available here.

Guadamuz, J. S., & Qato, D. (2023, June). Medicare Part D Preferred Pharmacy Networks and Risk of Pharmacy Closure, 2014-2022. Health Affairs.

States are likely to pursue PBM legislation in the absence of federal action, Joyce says

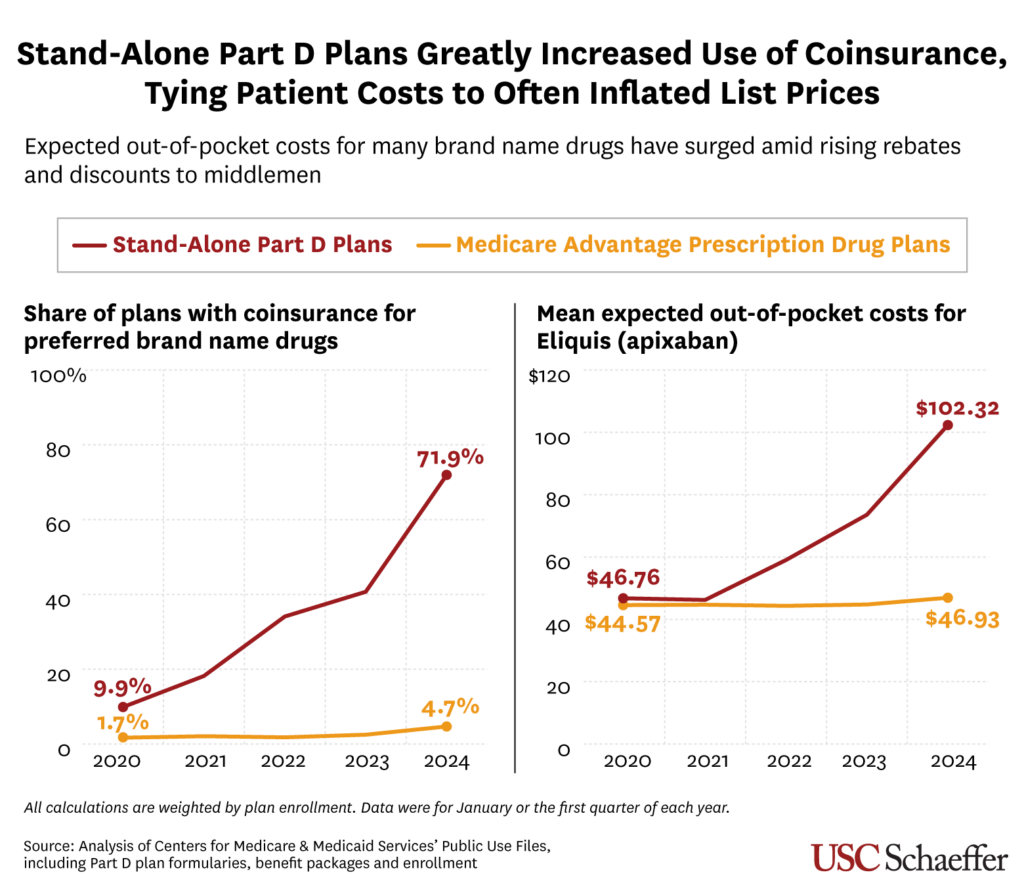

Cost Sharing for Preferred Branded Drugs in Medicare Part D

Most individuals in the US are concerned about prescription drug affordability. For patients facing co-insurance (a percentage of the drug price), out-of-pocket burden increases when list prices increase, as they have for brand-name drugs over the last decade. Manufacturer rebates and discounts, which have also increased, reduce net drug prices but are rarely shared with patients at the pharmacy counter. Moreover, growing rebates and discounts may further increase list prices, exacerbating out-of-pocket burden for patients with co-insurance. Patients with co-payments, which are flat fees, are largely shielded from these dynamics.

The full study can be viewed at JAMA. A press release on the study is available here.

Trish E, Blaylock B, Van Nuys K. Cost Sharing for Preferred Branded Drugs in Medicare Part D. JAMA. Published online February 14, 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.28092

Medicare Beneficiaries Face Much Higher Drug Costs as Plans Quickly Shift to Coinsurance

Most stand-alone Part D plans now link out-of-pocket costs of many brand name drugs to list prices, which are often artificially inflated

Expected out of-pocket costs for commonly prescribed brand name medications have grown substantially for Medicare Part D beneficiaries as drug plans increasingly tie patient costs to list prices, according to new research from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics published in JAMA.

Patients typically pay either a fixed dollar amount (known as a copayment) or a percentage of a drug’s list price (known as coinsurance), depending on their plan design. The researchers examined expected patient costs for preferred brand name drugs often lacking generic equivalents.

The share of stand-alone Part D prescription drug plans using coinsurance for preferred branded drugs sharply increased from 9.9% in 2020 to 71.9% in 2024, researchers found. By comparison, fewer than 5% of drug plans offered through more comprehensive Medicare Advantage coverage used coinsurance for preferred branded drugs last year.

As a result, Medicare beneficiaries in stand-alone drug plans, which account for 43% of the Part D market, are increasingly exposed to rising list prices. The coinsurance amount is usually around 25% of a drug’s price before any rebates or discounts negotiated by a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) or health plan are applied.

While rebates and discounts have also been increasing in recent years, those savings usually go to PBMs and health plans, rarely benefitting patients directly. Furthermore, steeper rebates and discounts demanded by PBMs may result in higher list prices, increasing the costs faced by patients with coinsurance.

“More and more Medicare beneficiaries who are taking highly rebated drugs are bearing the burden of artificially inflated list prices at the pharmacy counter,” said lead author Erin Trish, co-director of the Schaeffer Center and associate professor of pharmaceutical and health economics at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “They are paying more out of pocket and generating rebates that subsidize premiums for everyone else. That is the opposite of how insurance is supposed to work.”

Average expected costs more than double for some drugs

The study highlights the blockbuster blood thinner Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), which is taken by nearly 4 million Medicare beneficiaries and in 2024 had a list price of about $550 per month – within the typical range for branded, non-specialty drugs. The drug’s mean pharmacy cost, which is similar to list price, grew by 22% between 2020 and 2024, while its estimated Part D rebates recently averaged 45%.

Over that time, Eliquis’s average expected out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries in stand-alone Part D plans more than doubled, from $46.76 to $102.32, as the share of plans using coinsurance for the drug increased from 10.7% to 75%.

For those in Medicare Advantage drug plans, however, the average expected out-of-pocket cost for Eliquis increased just slightly from $44.57 to $46.93 between 2020 and 2024. Only 5% of Medicare Advantage plans used coinsurance for Eliquis last year.

Meanwhile, average expected out-of-pocket costs in stand-alone Part D plans also increased substantially for other common preferred branded drugs. Like Eliquis, some saw increases of more than double, including:

- Trulicity (dulaglutide) for Type 2 diabetes, from $54.04 to $128.43

- Xarelto (rivaroxaban) for blood clots, from $46.54 to $94.50

- Ozempic (semaglutide) for Type 2 diabetes (and other indications), from $56.95 to $135.43.

“Medicare beneficiaries are often blindsided when they suddenly have to pay much more for the same drug they may have been taking for years,” Trish said. “While Part D’s new out-of-pocket cap will help beneficiaries over the full year, that initial sticker shock could make it harder for them to maintain their prescription, potentially leading to worse health outcomes.”

About the study

Researchers calculated coinsurance and copayment amounts using public data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, including information on Part D formularies, benefit packages and enrollment. All calculations were weighted by plan enrollment and did not account for plan limits on out-of-pocket costs.

The study was co-authored by Schaeffer Senior Scholar Karen Van Nuys and Barbara Blaylock, founder of Blaylock Health Economics LLC. The research was supported by the Schaeffer Center. Please see the study for authors’ conflict of interest disclosures.

Eye on PBMs

Following the Money

Schaeffer research reveals how inefficiencies in the drug supply chain increase costs and limit access

Our Research on PBMsSmaller PBMs are facing challenges gaining market share, Joyce says

Sood explains why many states capped insulin costs

Testimony on the Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Editor’s Note: The following is testimony delivered by Karen Van Nuys to the U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust on Sept. 11, 2024. More information about the hearing can be found here.

Key Points

- The PBM industry is highly concentrated and vertically integrated: Three PBMs control about 80% of the market, raising concerns about limited competition and innovation. Major PBMs are part of conglomerates including insurers, pharmacies, and healthcare providers, creating potential conflicts of interest and opportunities for self-dealing.

- This market structure allows for problematic drug pricing practices: PBMs often increase costs for generic drugs, inflate brand drug list prices through the rebate system, steer patients to higher- rather than lower-cost drugs, and engage in opaque spread pricing. These practices obscure drugs’ true costs and lead to higher drug expenditures.

- PBMs’ unique market powers can impact patient access to medications: PBMs are increasingly restricting patient access to therapies through utilization management policies like prior authorization and formulary exclusions.

- As a result, many stakeholders are negatively impacted: These practices negatively affect federal programs, employers, consumers, and uninsured individuals by increasing costs and potentially reducing access to medications.

- Policy recommendations: Suggestions include increasing transparency, reevaluating the rebate system, scrutinizing vertical integration, and better aligning PBM incentives with patient and payer interests.

Full testimony is available here.

Joyce explains how independent pharmacies are being squeezed by PBM practices

Pharmacy Benefit Manager Market Concentration for Prescriptions Filled at US Retail Pharmacies

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play an important role in financing and delivering prescription drugs for health insurers, including designing formularies and pharmacy networks, negotiating drug prices, and reimbursing pharmacies.1 Despite evidence that 3 PBMs (CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx) accounted for 79% of prescriptions in the US in 20232 and growing concerns about the role of the highly concentrated PBM market on rising out-of-pocket costs and pharmacy closures,3,4 information on whether and how PBM concentration varies across payers is limited. This study analyzed PBM market concentration separately for commercial insurance, Medicare Part D, and Medicaid managed care in the US.

The full study can be viewed at JAMA.

Qato DM, Chen Y, Van Nuys K. Pharmacy Benefit Manager Market Concentration for Prescriptions Filled at US Retail Pharmacies. JAMA. Published online September 10, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.17332

Responding to Some ‘Inconvenient’ Truths About PBMs

This letter to the editor was originally published in STAT on Aug. 17, 2024.

This essay raises three presumed “facts” about pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

The first “fact” is that PBMs exist because insurers and self-insured employers use them. This is analogous to George Constanza’s contention that people will watch Seinfeld “because it’s on TV.” The authors contend that human resources departments seek proposals from PBMs through a competitive and transparent process, although they acknowledge that less sophisticated purchasers may need to hire biased brokers and consultants to assist them in signing self-serving contracts.

Having witnessed such negotiations first-hand, it is anything but a fair fight. Large PBMs often dazzle overmatched HR staff with promises of sophisticated algorithms that catch the smallest errors and disease management programs that will all but eradicate absenteeism, all while generating enough rebate dollars to fund a lavish holiday party. A few weeks later a phone-book sized contract will arrive, in English, but equally uninterpretable in any language. To call this process competitive and transparent is hardly a fact.

The second “fact” the authors offer is that high drug prices are primarily due to two acts of Congress, not PBMs, who they contend are the last line of defense in restraining drug prices. The two acts — patents for new drug development and protection from anti-kickback regulations — are important and broadly accepted, although one can debate specifics. What is most off-putting is a lack of discussion on the role PBMs play in increasing drug prices. I would refer those interested in more detail to the recent FTC report cataloging PBM behaviors, ” Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies.”

In response to such criticisms, PBMs argue that drug prices would be higher in their absence. This is true not because they are efficient nor benevolent but rather because at their core they function as large group purchasing organizations. The largest PBMs negotiate on behalf of tens of millions of consumers and their size provides increased leverage in playing one manufacturer against another to obtain larger rebates. While pro-consumer in theory, the lack of transparency and inability of plan sponsors to assess how much PBMs generate in savings and how much they retain for themselves is the root issue, with plan sponsors and others having little to no ability to monitor PBM behavior.

Mattingly, Hyman, and Bai also ignore how PBMs’ thirst for larger rebates leads to higher drug prices. An executive of a large drug manufacturer said that during price negotiations a PBM representative said “if you raise your prices we will consider putting your drug on a lower (more favorable) tier.” They did not explicitly say raise your rebate, but the message was clear — increase the spread between the list and net price and we will reconsider your formulary status. The key is the degree to which negotiated discounts are passed on to plan sponsors and their members through reduced premiums and/or lower cost-sharing at the point-of-sale. PBMs provide valuable services and should be fairly compensated, but industry wide profits of $25 to $30 billion annually seem too high.

I have no argument with the authors’ third fact, which is that every player in the prescription drug supply chain wants to make money. This is true in U.S. health care markets more broadly, where private firms are simply responding to the demands of their shareholders and the financial incentives embedded in both commercial markets and government-funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Recent revelations of upcoding and over-billing by health insurers in the Medicare Advantage program underscore this point. As the authors note, PBMs do not act in the interest of their clients because they are neither required nor incentivized to do so.

So what can be done? One option is to regulate PBMs under the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. ERISA sets minimum standards for most voluntarily established pension and health plans in private industry to provide protection for individuals in those plans. In essence, federal regulators would require the PBMs to act in the best interests of their clients. Giving ERISA regulators oversight of PBMs would change much of what is wrong in the pharmaceutical supply chain. It would return PBMs to their original and still important role of efficiently administrating drug benefits.

— Geoffrey Joyce is director of health policy at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics at the University of Southern California.